Rachael M. Benavidez

Adjunct Lecturer, English

Assistant to the Directors of First Year Writing

Checklist for Online Lesson and Lesson Plan for Detailed Textual P-A-S Outline

The integration of multimodal assignments in First Year Writing (FYW) courses draws on the development and practices that facilitate entering the conversation of academic writing using multiple forms of semiotic expression. As a FYW instructor with technological experience and who is interested in instructional design, the idea of multimodal composition assignments in an online or hybrid environment is a given.

However, in encouraging the development of multimodal assignments, it’s necessary to demonstrate what multimodal assignments bring to the conversation of academic writing and the ways in which they engage students—with minimal technological expertise (on our part and theirs). Before I discuss pedagogy, I’m going to review some rationale and best practices from the experts that influenced my thinking.

What is Multimodal Composing?

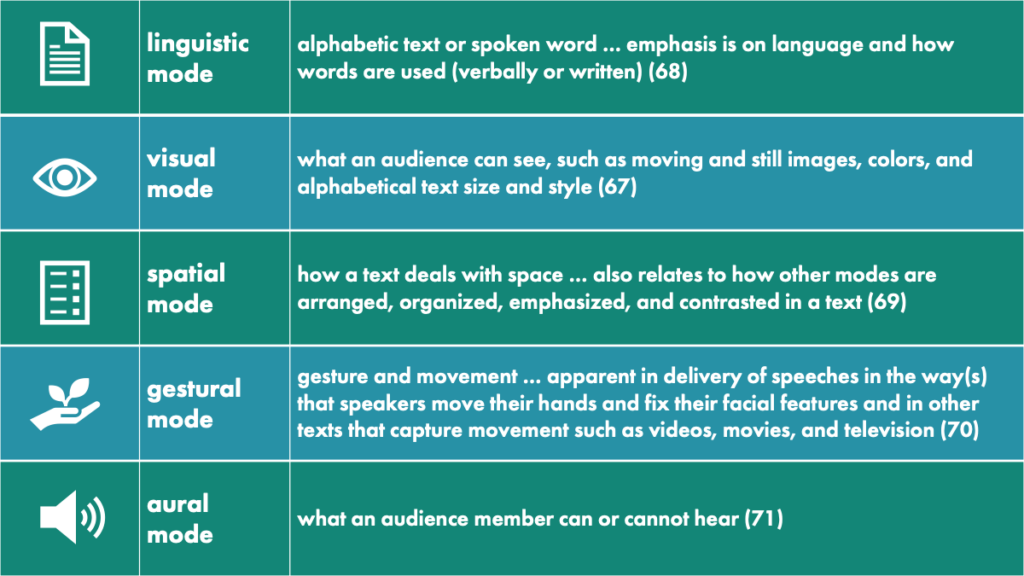

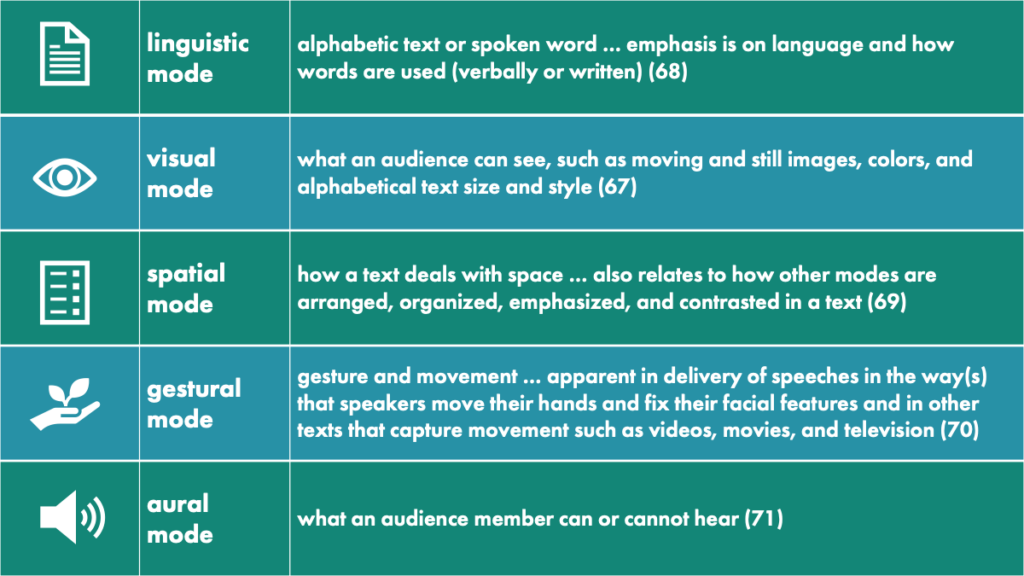

Multimodal composing involves multiple modes of communication. In their 1996 Harvard Educational Review article, “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” the New London Group argue that “multiplicity of communications channels and increasing cultural and linguistic diversity in the world today call for a much broader view of literacy than portrayed by traditional language-based approaches” (60). They define five modes of communication or “metalanguages that describe and explain patterns of meaning”: linguistic, visual, spatial, gestural, and multimodal (78).

The delivery of those modes can take different forms and is more informally explained in “An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing” by Melanie Gagich (67-72):

Note that the graphic employs three of the five modes and a fourth if a screen reader is reading the alternate text.

“Doing” Multimodal Writing

As with the graphic, the “traditional” FYW essay in MLA format employs linguistic, visual, and spatial modes. The words on the page communicate, the visual style and formatting of the text is set according to MLA of 12-point type, and the text is spatially organized by double-spaced text with specific formatting i.e. emphasis to identify a source citation as a book or an “article,” and page citation (##). In other words, we’re already employing multiple modes.

Many FYW instructors incorporate multimodal analysis into our courses, such as essays that require analysis of multiple forms of media. For example, in my own FYW courses, students analyze cultural representation in a film and cultural bias in an advertisement.

However, in order for students to go beyond analyzing the choices of others, we must instruct them in how to actively make their own through the experiential practice of multimodal composition and multiple modes of expression to convey semiotic meaning.

Why Multimodal Composition?

In “Thinking About Multimodality,” Takayoshi and Selfe provide points on their reasoning for multimodal assignments, the first of which is:

“In an increasingly technological world, students need to be experienced and skilled not only in reading (consuming) texts employing multiple modalities, but also in composing in multiple modalities, if they hope to communicate successfully within the digital communication networks that characterize workplaces, schools, civic life, and span traditional cultural, national, and geopolitical borders” (3).

FYW teaches students how to enter the conversation of academic writing, so the work of our courses goes beyond the course’s required essays. Technological tools that will be valuable to students in future courses—and beyond college— in the form of multimodal assignments are a form of social justice that prepare students for global citizenship.

Diverse Ways to Engage Students

All FYW instructors seek ways to actively engage students in their academic writing practices and the work of the course. Teaching FYW online offers instructors the opportunity to take advantage of the expansive and diverse set of tools to compose in multiple modalities in order to go beyond the textual essay.

Takayoshi and Selfe also argue:

“The authoring of compositions that include still images, animations, video, and audio—although intellectually demanding and time consuming—is also engaging” (4).

In order to develop engaging and dynamic assignments, we need to consider how Online Writing Instruction (OWI) allows to do that work. In “Grounding Principles of OWI,” Beth L. Hewitt asserts that:

Online Writing Instruction (OWI) Principle 3: “Appropriate composition teaching / learning strategies should be developed for the unique features of the online instructional environment” (Hewett 55).

In other words, what are the benefits of teaching FYW online in terms of the use of technological tools that may not be available to us in an in-person (only) learning environment? How do they engage students in ways that actively involve them in their writing?

Developing Multimodal Writing Assignments

The Researched Argument Essay Presentation Assignment

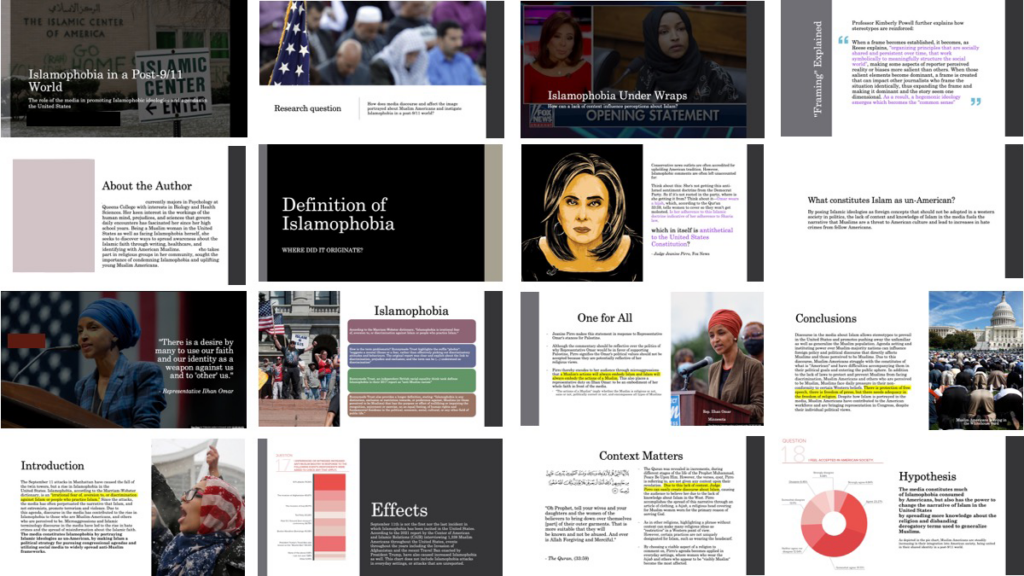

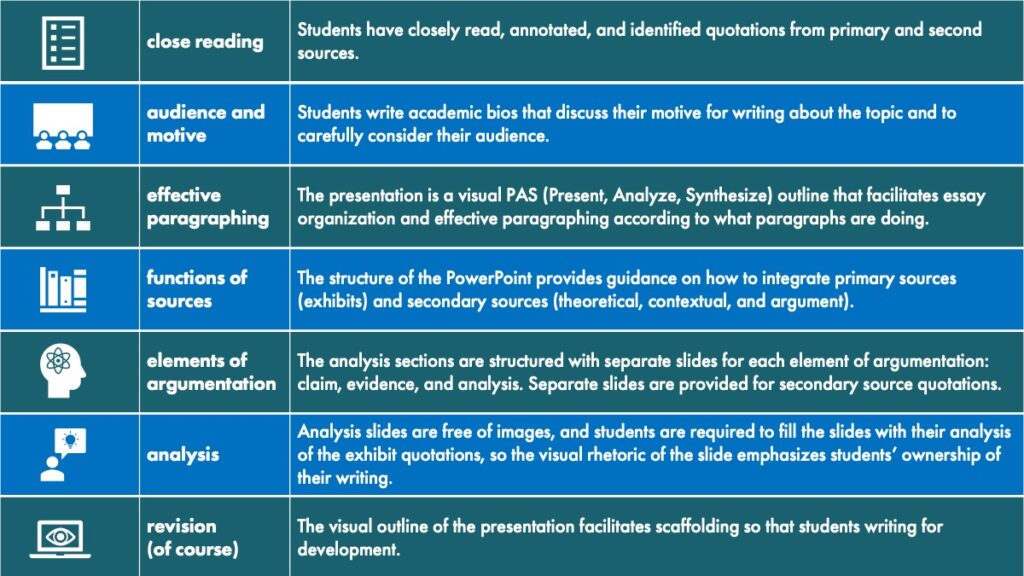

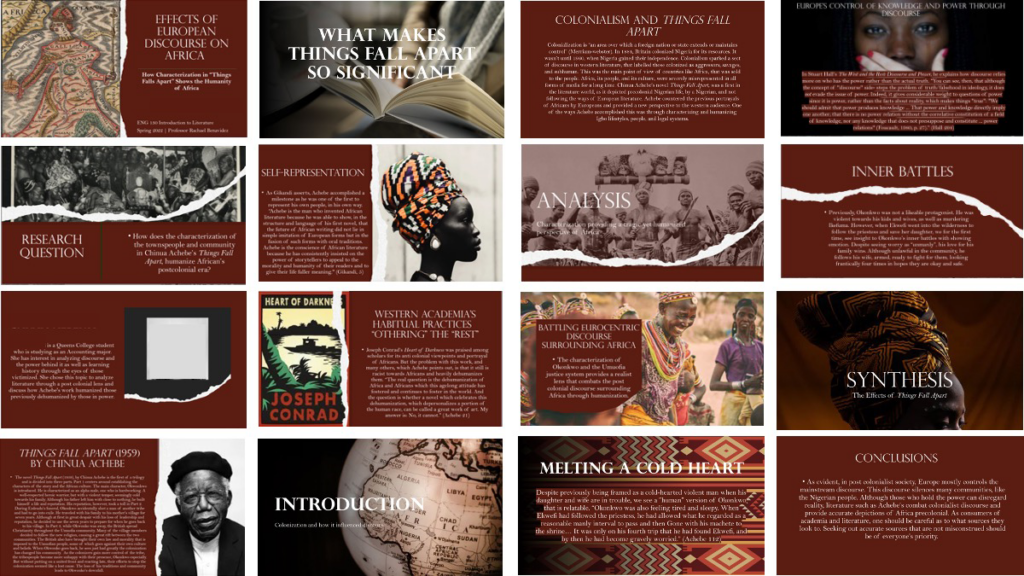

In the Fall 2021 semester, I worked with FYW Associate Director Christopher Williams to develop a multimodal assignment for my College Writing I course, Critically Reading and Responding to Media for Essay 3: Researched Argument. In the Spring 2022 semester, I developed a similar assignment for my Writing About Literature course. Selections from student assignments are provided as samples at the end of this post.

For the essay assignments, students use a variety of contextual, theoretical, and argument sources to produce an insightful argument that answers an interpretive question that they raise about the exhibit(s). In addition to textual analysis, the multimodal aspect of a PowerPoint presentation requires students to identify images that make relevant, rhetorical connections in order contextualize and to develop their analysis. They also had the option to record voiceover and make a video but chose to do the PowerPoint only. A future endeavor, perhaps.

Focus Assignments on Course Goals and Writing Practices

When working with Chris on developing the multimodal assignments, he asked a few guiding questions:

- What specific academic writing practices does a PowerPoint facilitate?

- What does it bring to the assignment that a ‘traditional’ essay doesn’t in terms of engaging students and reaching course goals?

- How much time will you need to spend on teaching technology (instead of writing)?

His questions are essential to any FYW course multimodal assignment.

OWI Principle 2: “An online writing course should focus on writing and not on technology orientation or teaching students how to use learning and other technologies” (Hewett 51).

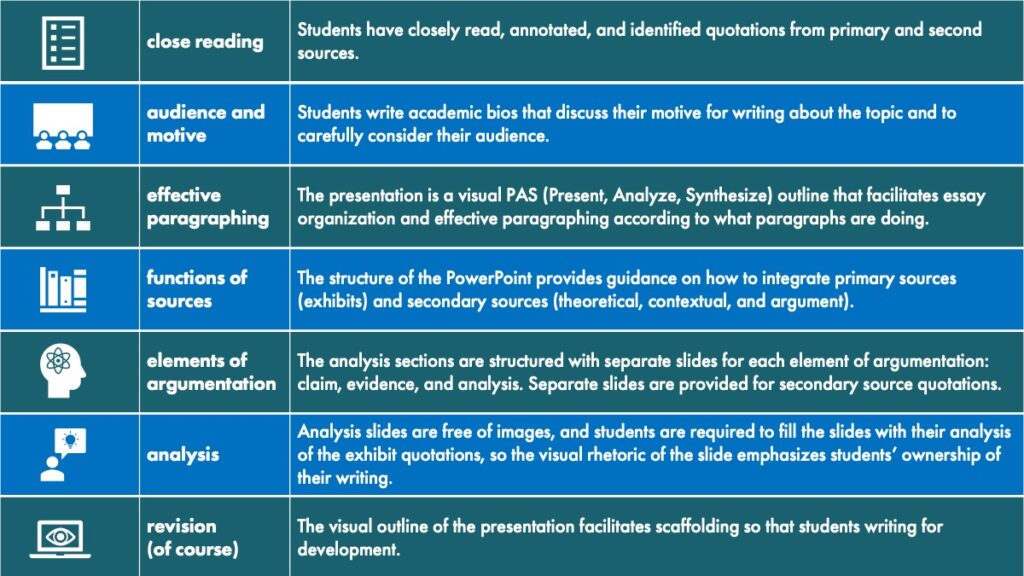

The PowerPoint presentation that I assigned focused on course learning goals through developing specific writing practices. A few examples:

The assignments that we develop must facilitate focus on specific writing practices that facilitate students’ ability to reach course learning goals—that’s what we do here.

Ease of Use—For Instructors and Students

Since our focus is teaching writing practices, rather than tech support, ideally, how to use the tool for the assignment can be conveyed in a brief lesson of twenty minutes (or less).

OWI Principle 10: “Students should be prepared by the institution and their teachers for the unique technological and pedagogical components of OWI” (Hewett 72).

You will need to work with students to structure their work and to spend some time on the technological tool, so consider technological skills—yours and your students’. I’m familiar with PowerPoint and could easily develop a template that focuses on writing practices and show students how to use it in a brief lesson. That lesson allowed me to clearly convey to students how use of the PowerPoint develops their writing practices and walked them through the process.

Accessibility and Equity—Assignments and Materials

Teaching online and multimodal assignments addresses diverse learning styles by providing multiple means of engagement, representation, action and expression (Universal Design for Learning or UDL). Our materials and assignments should be accessible to all of our students.

OWI Principle 1: “Online writing instruction should be universally inclusive and accessible” (Hewett 44).

American with Disabilities Act (ADA) Compliance

As we consider tech tools for assignments, it’s essential that our materials to be accessible, i.e. close captioning for videos, documents that are readable by screen readers, and transcripts for audio only files.

Equitable Access to Technological Tools and Media

As we consider tech tools for assignments, the tools and media that we select must be widely available at no costs to students. I chose PowerPoint because Microsoft Office 365 is included in student tuition, which means that no student needs to purchase any software or fancy equipment to complete the assignment.

Always Return to Course Goals and Writing Practices

When making decisions about tech tools and modes of expression, the main questions that we want to constantly return to focus on the writing practices. Ultimately, FYW instructors want students to be critically aware of their own rhetorical choices. When thinking through the myriad of tools, we must always come back to the specific writing practices that the multimodal assignment helps students to develop. In many ways, we apply the same strong pedagogical strategies that we do for any assignment.

Backward Design, Sequencing, and Scaffolding

Principles of backward design (Wiggins and McTighe) are essential to developing assignments that carefully consider course and assignment goals and scaffolding that facilitate student practice. The questions that you pose of how the multimodal assignment facilitates the development of writing practices will be unique to the assignment that you develop.

Develop essay progression assignments that facilitate student ability to complete the multimodal assignment and provide practices for and engage students in diverse forms of semiotic literacy.

For example, in the second essay progression, students:

- Identified and color coded the elements of argumentation in their analysis paragraphs.

- Practiced effective paragraphing by developing a PAS outline of their essays.

- Distinguished the function of a primary versus a secondary (contextual) source.

In third essay progression, students developed a detailed PAS outline, identified source quotations, and developed a complete Works Cited page. The progression introduces additional secondary source types (theoretical and argument), but students are building on previous knowledge. In other words, the only completely new concept being introduced with the third progression multimodal assignment was visual rhetoric.

Starting small is absolutely okay. A multimodal assignment can be a single, scaffolded step or two in the essay progression sequencing. Instructors might also consider how to integrate visual rhetoric into low-stakes assignments and/or earlier progressions. Prior to working on the multimodal assignments, it’s essential to introduce students to specific writing practices and strategies to allow them to practice them before working on a high-stakes multimodal assignment.

Provide Models

Develop multimodal materials. I’m not in any way proposing that every FYW be an instructional designer, graphic designer, or filmmaker. What I am proposing is that instructors carefully consider the multimodal rhetoric of their course materials. Many of the tools suggested are useful in creating materials, are free, and are easy to use.

Model assignments. While I have model textual essays, in the first semester that I taught the multimodal assignment, I didn’t have a model presentation, so I worked on my own presentation at the same time as the students. It had an added layer of value: when I asked students what challenges they were having in developing their essays and was answered with silence, I was able to speak about my own. My reflection sparked conversation when students realized that the challenges were “normal” at the specific point in the (non-linear) writing process.

Evaluation

As with any assignment, it’s essential to clearly state how students are being evaluated on aspects of multimodality—in addition to the academic writing practices that are typically included (thesis, analysis, organization, citation, etc.). However, it doesn’t have to be and shouldn’t be complicated. Additionally, we need to be flexible and shouldn’t expect students to be technological experts. Mainly, the evaluation of the aspect of modality must be directly connected to academic writing practices.

Consider How the Mode of Expression Works with the Course Theme

Most FYW courses have a theme that propels the course. For example, themes in the Queens College FYW program include Monsters, Language and Literacy, Visual Culture, including photography, art, and film, Creativity, and Cultural Identity. The course theme provides a foundation for determining multimodal assignments, tools, genre, and media.

In April 2022, I co-presented on a Pedagogy of Kindness Panel entitled “Alternative Assessments: Ungrading and Assignment Scaffolding” with Lecturer in English Lindsey Albracht and Associate Professor of History Kara Schlichting. Professor Schlichting provided examples for remixing the “traditional” essay into visual art, such as a poster or comic, a museum exhibit plan, or a PSA. Her remixing ideas translate to FYW assignments and that draw on the course theme.

For example, the QC FYW Visual Art syllabus theme encourages instructors to arrange a class trip to a Queens or New York City museum. A multimodal assignment that asks students to visually dissect the elements of a work of art in a poster form allows for a deeper analysis of the work. Analysis of public artwork might also be actualized as TED Talk to employ multiple modes of communication. A more advanced assignment might ask students to curate a public exhibition and explain their choices. Another version of the Visual Art theme explores the graphic novel, so students might create their own.

There are numerous possibilities, but what I’m suggesting is that the modes of expression reflect the theme of the course in order to convey semiotic meaning, which facilitates students’ ability to make connections to learning and their own rhetorical choices.

Involve Students in Assignment Options

Professor Schlichting encourages class discussion to determine options for modes of expression. Suggest a few options and have students discuss how and why their choices are the most appropriate as a metacognitive exercise and as another way to actively engage them in the course.

Tools and Resources to Engage a Writing Community

There are numerous free tools that are easily integrated. The QC Center for Teaching and Learning is a great resource for finding tools, but here are a few suggestions that will hopefully help you to engage a writing community and develop specific writing practices.

- Integrate visual rhetoric and/or aural modes into course blogs. Blogs are integrated into LMS’s, which means that instructions are already available to instructors and students. Work with students

- Integrate video tools humanize discussion boards to actively engage in a writing community. FlipGrid and VoiceThread are tools that allow students to post video links to the LMS. Make sure to start the conversation with your own video as a model. The tools are also great for peer review.

- SoundCloud is a free audio tool that is also a great tool for peer review and for translation assignments. It allow you to provide verbal assignment to accompany textual instructions.

- Canva provides free templates for visual assignments, such as infographics, brochures (PSAs), social media posts, posters, and presentations. It’s relatively easy to use.

- Everyone is familiar with YouTube, which is free with a Gmail account. Instructors and students can post public, private, or unlisted videos. Make sure to consider accessibility with close captioning.

- Openly licensed materials, such as images, texts, and video provide a lesson in citation and fair use and also in thinking through students’ public scholarship. The QC Library’s Digital Scholarship page offers numerous suggestions.

- PowerPoint goes beyond text and images. Narration can be recorded and include video of the presenter. The file can be saved or exported as a video and uploaded to YouTube.

Keep Posing Questions

As you think about multimodal assignments, keep posing questions on how their integration supports learning goals and writing practices and engages students in multiple forms of semiotic expression. I think that you’ll find that your students aren’t the only ones who are engaged by multimodal assignments.

Sample Multimodal Assignments from My (Amazing) Students

College Writing I Course: Islamophobia in the Media a Post-9/11 World

Writing About Literature Course: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1959)

Annotated Bibliography

The following annotated bibliography was developed with the purpose of developing multimodal assignments for FYW courses that facilitate reaching course learning objectives through strong pedagogy, the development of strong writing practices, and equity in access to learning.

It is organized in two sections: Pedagogical Best Practices, which are important considerations in any teaching modality; and Online Writing Instruction (OWI) and Multimodal Assignments, which considers foundational practices for teaching writing online that facilitate thinking on how online instruction works in conversation with multimodal assignments.

Pedagogical Best Practices

- Bowen, Ryan S. “Understanding by Design,” Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching, 2017. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/.

Backward design is essential to developing assignments and scaffolding lesson plans. Ryan Bowen provides an overview of Wiggins’s and McTighe’s essential principles of “Backward Design” on the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching website, including benefits and stages. The site also includes a brief video of Wiggins discussing the “planning framework” of backward design. A template for applying the principles is available for download and assists instructors in thinking through the stages of backward design, beginning with the goal(s) and culminating with the lesson plan. For further reading, see Wiggins, Grant, and Jay. McTighe. “Backward Design,” Understanding by Design, ASCD, 1998.

- Cazden, Courtney, Cope, Bill, et al. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” Harvard Educational Review, Spring 1996, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 60-92.

In the scholarly article “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” the New London Group argue that “multiplicity of communications channels and increasing cultural and linguistic diversity in the world today call for a much broader view of literacy than portrayed by traditional language-based approaches,” one that counters the “formalized, monolingual, monocultural, and rule-governed forms of language” (60). Their argument on multiliteracies centers on the intersectionality of cultural and linguistic diversity and multimedia technologies and the ‘othering’ discourses that limit educational opportunities. While the article may seem somewhat outdated, it laid the groundwork for how we understand multimodal assignments and defined five modes of communication or “metalanguages that describe and explain patterns of meaning”: linguistic, visual, spatial, gestural, and multimodal, that modern writing instructors apply to multimodal assignments (78). The article also speaks to the emerging understanding of multimodal writing as a form of social justice.

Best Practices for Teaching Online

- “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2.,” CAST, 2018. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles are fundamental to any course to ensure equity in learning. The Guidelines are a “framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn” and address the ways in which instructors provide multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression. Each of the three criteria is defined in terms of how options for access, building, and internalizing work toward specific goals. While it may not be realistic for instructors to apply all of the criteria, UDL provides target points for reflection for instructors as they develop courses, materials, and assignments.

Online Writing Instruction (OWI) and Multimodal Assignments

- Gagich, Melanie. “An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing,” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 3. WAC Clearinghouse. 2020. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces3/gagich.pdf.

Gagich defines multimodal texts and provides examples using the five modes of communication asserted by the New London Group (linguistic, visual, spatial, gestural, and multimodal). With attention to the rhetorical situation of the multimodal text and what it’s “doing,” Gagich provides strategies for creating and scaffolding multimodal assignments. Instructors will find the article useful in terms of creating multimodal materials and developing assignments.

- Hewett, Beth L., & Kevin Eric DePew (Eds.). (2015). Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction. The WAC Clearinghouse; Parlor Press. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2015.0650

Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction is indispensable in developing OWI programs and courses. My focus is on two specific chapters that provide principles for teaching the courses and for teaching multimodal assignments.

- Beth L. Hewett’s Chapter 1 “Grounding Principles of OWI” in Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction adds to the discussion of the CCCC Committee for Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction: “A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction (OWI.” The chapter examines fifteen OWI principles important to understanding fundamental similarities and differences between in-person and online courses. For each of the principles, a discussion of the rationale provides guidance for proactive implementation in hybrid and online writing courses. Aimed at instructors and FYW programs, it focuses specific attention on accessibility and equity in terms of student access (and faculty labor and professional development) and will be useful in understanding how to develop pedagogy that supports student learning online.

- Kristine L. Blair’s Chapter 15 “Teaching Multimodal Assignments in OWI Contexts,” in the same publication provides strategies for migrating textual essay assignments into multimodal assignments. Blair’s focus is on the “whats, hows, and whys of transforming OWI from a text-centric composing space for our students to one that integrates multimodal elements for students and instructors in as viable, accessible, and introductory a way as possible” (480). Blair examines assignment modes and discusses how they function in terms of writing practices. Instructors will likely find her article particularly useful in terms of thinking through how potential low-stakes assignments might work in their courses.

- Selfe, Richard J., and Cynthia L. Selfe. “‘Convince Me!’ Valuing Multimodal Literacies and Composing Public Service Announcements.” Theory Into Practice, vol. 47, no. 2, 2008, pp. 83–92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071528. Accessed 20 May 2022.

Richard Selfe and Cynthia Selfe discuss “why teachers need to adapt an increasingly broad understanding of the roles that different composing modalities play in contemporary communication” (83). They begin by addressing arguments that will convince writing instructors of the value of multimodal assignments (85-86). They provide a multimodal PSA assignment sequence and explain their strengths as multimodal assignments. Additionally, they provide examples and questions for students and instructors, making it more easily adapted for a FYW course.

- Takayoshi, Pamela and Cynthia L. Selfe. “Thinking About Multimodality,” Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia L. Selfe, Hampton Press, Inc. 2007, pp. 1-12.

In their influential discussion of multimodal composition, Takyoshi and Selfe provide five specific points for understanding the importance of multimodal composition and address questions and concerns of composition instructors who may be wrestling with the usefulness of multimodal composition, such as ‘Are we really teaching writing with multimodal assignments?’. Instructors will find the chapter useful in terms of answering those how and why questions but also in terms of provoking broad questions on how they might approach developing multimodal composition assignments for their own courses.